Six Lucky Fun Facts About Chinese Lunar New Year

By David Nakayama - Published February 25, 2021

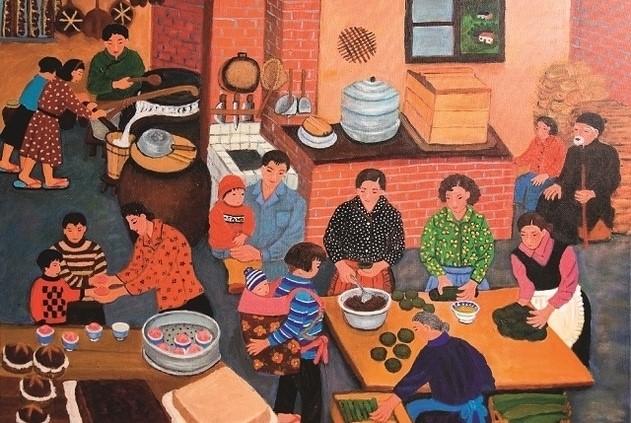

Image Source: “Chinese New Year in Taiwan” CommonWealth Magazine

Image Source: “Chinese New Year in Taiwan” CommonWealth Magazine

By David Nakayama, DET Corp Comms

Chinese New Year (農曆新年) or Spring Festival (春節) is an ancient Chinese festival that begins on the new moon that appears between 21 January and 20 February. It’s celebrated in many countries with cultural ties to China including Thailand.

At this time, many Thais also enjoy putting up decorations, sharing a feast with the extended family and exchanging red envelopes (Ang Pao) with wishes for health and gold to fill a hall. But did Ah Gong or Ah Mah from the old country tell you the meaning behind all the fanfare?

Let’s find out what Chinese New Year traditions and events are all about with our Lucky 6 Chinese New Year Fun Facts.

1. Bright red and firecrackers drive away misfortune

.jpg) Image Source: ChineseNewYear.net

Image Source: ChineseNewYear.net

According to legend, a monster called the Nian (年獸) would come out once a year at Chinese New Year to eat villagers in the middle of the night. An old man or child put red papers up and set off firecrackers that scared the Nian away.

Nowadays people wear red clothes, put up red scrolls around their doors and fire off strings of firecrackers to scare away evil spirits.

2. Giving money brings luck to everyone

.jpg) Image Source: BBC

Image Source: BBC

Red envelopes with money (紅包) symbolize good luck and help ward off evil spirits. In Southern China, married people give red envelopes to unmarried people and children. In Northern China, red envelopes elders give them to the younger people.

Be sure to put crisp new banknotes inside the red envelopes you give and avoid opening the envelopes in front of others. Put lucky amounts inside that begin with even numbers inside such as 8 (八) for wealth, 6 (六) meaning smooth. Never put in 4 (四) which sounds the same as death and avoid odd numbers.

3. Flipping fortune over brings it onto your home

Image Source: CGTN

Image Source: CGTN

At Chinese New Year we hang a red diamond-shaped with the Chinese character for “fortune” (福) at the home entrances. Many people hang the character for fortune upside down because the Chinese word for “upside-down” (倒) sounds the same as “arrive” in Chinese (到) so this means of luck, happiness, and prosperity is arriving in your home.

4. Chinese New Year foods are different in each region

Image Source: Travel China Guide

In North China, Chinese New Year feasts must have piles of steaming hot dumplings (饺子) which the whole family gathers to hand-make. Dad rolls out the skins and everyone from granny to the kids helps fill and wrap the dumplings for boiling.

In South China (where most Thai Chinese originate) people like giving out Chinese New Year Cakes made from sticky rice (年糕). These cakes come in different forms from Fujian to Guangdong provinces and the countries of Southeast Asia with large Hakka and Cantonese communities.

5. The biggest home trip in the world

.jpg) Image Source: Global Times China

Image Source: Global Times China

It may be hard for Thais to imagine just how hard it is to get home for the Chinese New Year in a huge country with the largest population in the world. China’s home trip season or “Spring Travel” (春運) is a 40-day period that is the world's largest annual migration with millions of Chinese taking roundtrips from their workplaces on the coast to their hometowns hundreds or even thousands of kilometers upcountry.

In 2019 before COVID, an estimated three billion home trips were taken during the holidays. Nowadays Chinese can take a plane or high-speed train, but until recently there was no choice but to wait for days outside the train station to buy a ticket only to then endure more days packed in crowded slow trains inching through the frozen countryside.

6. Spring Festival marks the end of winter freeze and the start of spring warmth .jpg)

Image Source: China Daily

Spring Festival marks the end of winter and the beginning of the spring season in the lunisolar Chinese calendar. Thais might not feel any winter or spring in the year-long tropical climate, but many Chinese have to endure months of ice and snow and cross frozen terrain to arrive home and visit relatives.

In central and upper-south Chinese provinces without state-established central heating systems of the north, many people spend the festival wearing heavy jackets inside their chilly homes as they snack on sunflower seeds and look forward to the end of yet another bitter hard winter.